I want to talk about Origins in the context of visual invention and the evolution of Christian iconography.

To find out more of the backstory (for example, why the left-hand panel, christened Yo Mama, has shown alone until now) I refer you to the articles below.

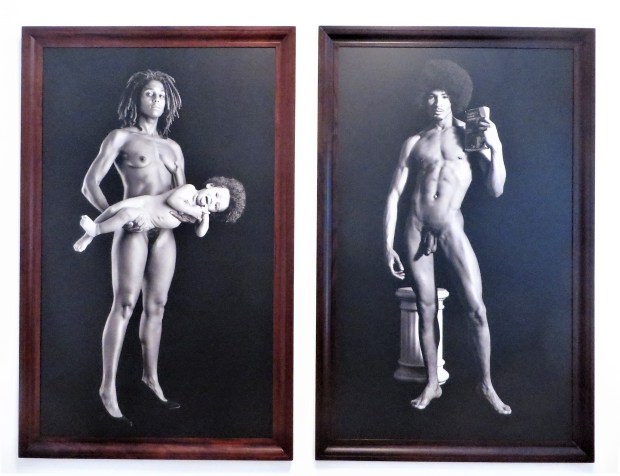

Though I had spent time in their presence, I was surprised to learn that these pictures are only seven feet tall—they loom much larger than that. These images have other connections, one of which is to the Black is Beautiful movement in the 1960s, but their relationship to the history of picturing the holy family is undeniable, too.

I don’t think there’s a Catholic church that would show them today, which is a pity, and really, “Why not?”

Early pictures of the Madonna and child show them sitting stiffly; their relationship is hierarchical. The same position is apparent in Egyptian mother and child arrangements.

Mary loves Jesus!

No doubt mothers loved their children before the 1300s but at least no Western artist noticed—or thought it was important. The Duccio may not be the first depiction, but The Met calls it inaugural: “…his lyrical work inaugurates the grand tradition in Italian art of envisioning the sacred figures of the Madonna and Child in terms appropriated from real life.”

This idea, that a relationship that now seems so beautiful and obvious might be unseen or overlooked, gives a whole new meaning to art and how useful it might actually be to us. (The ¾ view in portraiture, attributed to Leonardo daVinci is another example of invention. Yes, I’m talking about the Mona Lisa.)

And to go back to the Met’s description for a moment—How do we know what’s “real life?” —before it is pictured, I mean.

In Origins, though he stands apart: there is no doubt who the father is; the fantasy of the virgin birth is dismissed; he is portrayed in full frontal nudity.

Based on Michelangelo’s David,—instead of a sling and a rock,he holds a book asserting that the cradle of culture is African.* Sensitive and intellectual, he recalls St. Luke—not Joseph, the not-father.

Although, who is a father—some angel that takes off or the man who puts food on the table and teaches you to throw a ball?

Also the baby points at him. I asked the artist if that was planned. She laughed at me for thinking it was possible to get a baby to do that.

The Mother is splendid and powerful— protective, but not fearful. Her most striking feature is her large and powerful hands, especially the right one that encircles the baby’s neck. She’s got you.

Those hands support the star of the show: they are the reason he laughs.

It’s very powerful the way Cox has pictured him—a little Jesus, or at least one of His avatars, at home in the world.

—CNQ

(*) From the Cathouse Proper press release:

In his hand he holds a well-worn copy of Cheikh Anta Diop’s revolutionary corrective to the West’s willful misunderstanding of ancient Egyptian history, “The African Origin of Civilization.”

The Brooklyn Rail: Jan Avgikos

https://brooklynrail.org/2019/10/artseen/Renee-Cox-Returned